On Monday, March 5th, Michael Shapiro, co-founder and first director of the Program in Jewish Culture & Society, returned to campus to speak about Wrestling With Shylock: Jewish Responses to The Merchant of Venice, in celebration of the essay collection with that name edited by Shapiro and Edna Nahshon and published by Cambridge University Press in 2017. Speaking to an attentive audience in Levis Faculty Center, Shapiro sketched in the origins of Shakespeare’s character and traced his changing presentation from Elizabethan times to the present.

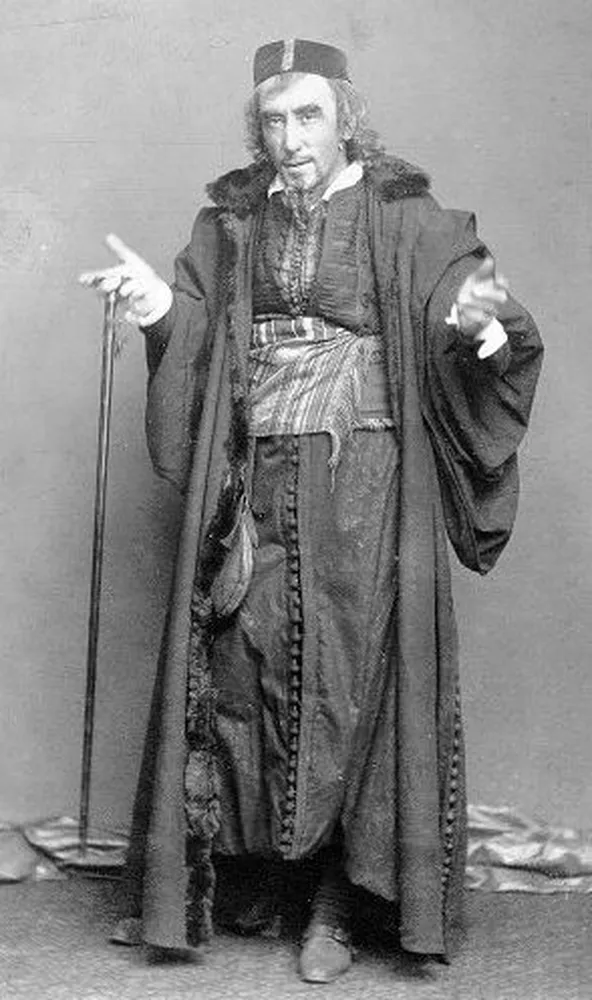

Shylock, Shapiro noted, is a much more complex character than the nameless “Jew” of Shakespeare’s source or other Jewish stage villains of the era, like Barabas in Christopher Marlowe’s The Jew of Malta. Though Shakespeare emphasizes Shylock’s comic stinginess and the legalistic thinking attributed to Jews by the apostle Paul, he grounds Shylock’s speech in Jewish ritual practice and scripture and presents him as a grieving husband, an abandoned father, and an articulate target of Christian hostility who asserts his own humanity in the face of persecution. While the question of Shakespeare’s original intentions cannot finally be answered, Shylock’s multi-faceted character has invited changing literary and dramatic interpretations as attitudes toward Jewishness and the Jewish situation evolve. Presented as a melodramatic villain of astonishing ferocity in the 18thcentury by Charles Macklin, Shylock was gradually humanized by the great 19thcentury actors Edmund Kean, Edwin Booth, and Henry Irving. These actors sometimes eliminated the fifth act of Shakespeare’s play, thereby ending it with Shylock’s tragic defeat. Irving looked on Shylock as “the type of a persecuted race” and motivated his vengefulness by stressing the betrayal of his daughter Jessica. Counterpointing these sympathetic portrayals of Shylock were 19thcentury burlesque theater versions that caricatured him as an old-clothes dealer or immigrant street peddler, a cousin of Dickens’ Fagin. Twentieth-century actors have drawn on these traditions in various ways, ranging from Sir Laurence Olivier’s attempt to recapture Irving’s Victorian Jewish gentleman to Warren Mitchell’s employment of a heavy Yiddish accent in the 1980 BBC television version and Anthony Sher’s conception of Shylock as “an Eastern Jew closer to his own Semitic roots” in the 1987 RSC production. In the latter two productions, Shylock’s otherness and his desire for vengeance were offset by heightening the violence of his forced conversion and the abuse he suffers at the hands of the lesser Venetians.

Shapiro also identified several other strategies in recent productions or literary adaptations that contextualize Shylock’s hostility to Antonio or complicate our response to him. One is to decenter Shylock by making his daughter Jessica’s story as important as his and to complicate the emotional relationship between them. For example, Henry Goodman’s Shylock in the 1999 National Theatre production was both a loving and an overly possessive father who drove his daughter to marry “out”; the ending focused on Jessica as she reprised the Hebrew song about a good wife they earlier sang together, her anguished face expressing regret and sorrow. Recent prose adaptations by writers like Erica Jong also explore Jessica’s plight as the immigrant’s daughter, belle juiveor schõne judin, forlorn wife or remorseful child, making her the protagonist of her own story. A second strategy is to reset the play in Fascist Germany or Italy, which insures that Shylock automatically becomes a sympathetic victim, as his Venetian persecutors evoke those responsible for the Holocaust. George Tabori’s 1966 Berkshire Theatre Festival went even further, presenting the play “As Performed in Theresienstadt” by Jewish prisoners for the entertainment of their Nazi guards; in successive curtain calls the actors were taken off as if to execution, leaving only a pile of clothes on stage at the end. A third strategy is to universalize the play’s Jewish-Christian conflict by mapping it onto other racial, religious, or ethnic antagonisms. Peter Sellar’s 1994 production set the play in Venice Beach, Los Angeles, casting Latinos as the macho male Venetians, Asian-Americans as Portia and her entourage,  and at the bottom of the social order, African-Americans as the Jewish characters. An interesting current example of this strategy is Shishir Kurup’s The Merchant ON Venice, first performed by the Silk Road Project in Chicago in 2007, then with appropriate changes as The Merchant of Vembleyin London in 2015, and now revived again in Chicago. Written in iambic pentameter, Kurup’s version depicts the conflict between a Muslim “Shylock” and his Hindu neighbors along Venice Boulevard in Culver City, Los Angeles, where old religious antagonisms among competing groups of South Asian immigrants aggravate current social and economic disparities.

and at the bottom of the social order, African-Americans as the Jewish characters. An interesting current example of this strategy is Shishir Kurup’s The Merchant ON Venice, first performed by the Silk Road Project in Chicago in 2007, then with appropriate changes as The Merchant of Vembleyin London in 2015, and now revived again in Chicago. Written in iambic pentameter, Kurup’s version depicts the conflict between a Muslim “Shylock” and his Hindu neighbors along Venice Boulevard in Culver City, Los Angeles, where old religious antagonisms among competing groups of South Asian immigrants aggravate current social and economic disparities.

Shapiro’s presentation gave the audience a new appreciation of Shakespeare’s play as a complex organism that continually opens new possibilities for interpretation. Shylock continues to evolve as actors, directors, and adapters respond to historical events like the Shoah and to social and political developments in the world outside the playhouse. Readers who want to explore Shylock’s transformations further will find the eighteen essays in Shapiro and Nahshon’s collection a valuable guide to The Merchant’s theatrical, literary, and artistic history.