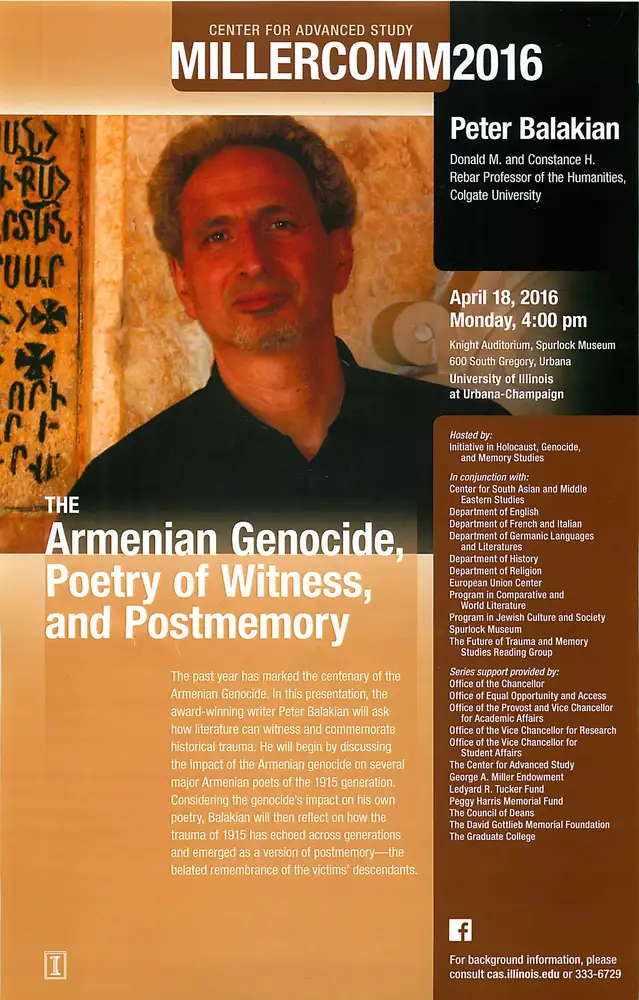

The Program in Jewish Culture and Society and the Initiative in Holocaust, Genocide, and Memory Studies organized a special visit from Peter Balakian, a 2016 Pulitzer Prize-winning Armenian American poet, memoirist, and foremost scholar on the Armenian Genocide. This visit included Balakian delivering the Center for Advanced Study (CAS)/MillerComm lecture “The Armenian Genocide, Poetry of Witness, and Postmemory” on April 18th, 2016, close to the 101st anniversary of the Armenian Genocide. Balakian’s visit generated insightful conversations on history, literature, memory, and artistic representation of genocide and trauma.

Balakian’s work offers scholarship, creative output, and communal activism coming together to secure social justice for victims of mass violence. As the Donald M. and Constance H. Rebar Professor of the Humanities at Colgate University, Balakian delineates the importance of witnessing, remembering, and learning about genocides, both inside and outside of the classroom. He also teaches several courses at Colgate on genocide and writing, specifically examining works on the Armenian Genocide and the Holocaust. Balakian was awarded the 2016 Pulitzer Prize in Poetry for his Ozone Journal, a poetry collection that deals, in part, with the speaker's memories of excavating the remains of Armenian Genocide victims in the Syrian Desert. During his time at the U of Illinois, Balakian underscored the need for excavating and studying difficult pasts and the need to elucidate histories of collective violence into the general consciousness.

In the culmination of his visit, Balakian’s lecture was equal parts academic, creative, and historical. First, Balakian turned to Yeghishe Charents’s poem “Dantesque Legend.” Charents wrote “Dantesque Legend” based on his experiences as an eighteen-year-old volunteer battalion fighter against the Ottoman military that was massacring Armenians. Balakian argued that in witnessing the atrocities and confronting the trauma through poetry, Charents “ingested violence” in his “stiff-eyed seeing of unimaginable cruelty and violence.” By categorizing Charents’s poem as an example of “poetry that ingests violence,” Balakian emphasized a poetry’s weaving together the complex layers of the traumatic event. Then, Balakian turned to three of his own poems—“The History of Armenia,” “Road to Aleppo, 1915,” and “For My Grandmother, Coming Back”—to discuss his own explorations of Armenian memory, generational transmission of trauma and memory, and poetics. Balakian’s grandmother, a death march survivor, filed a human rights lawsuit against the Turkish government. Balakian learned about the document, which he weaves into his poem “The Claim,” years after his grandmother passed away, and this discovery prompted a lyrical impulse to try and retrieve something of what was lost. In these poems, Balakian explores his grandmother’s recall of the Genocide, confronts the harsh reality of deportations and death marches, and imagines a return to a lost homeland.

Balakian also fostered various conversations across campus. Balakian met with Creative Writing MFA students to discuss the challenges in writing about trauma, violence, and politics as well as pedagogical strategies related to teaching undergraduates about genocide; he also visited with graduate students from The Future of Trauma and Memory Studies Reading Group. At this meeting we discussed a selection of Balakian’s poems, a chapter from his memoir Black Dog of Fate, and a piece from his new essay collection, Vise and Shadow. Balakian facilitated cross-disciplinary dialogues that left members energized and excited. During a meeting with the Armenian Association of the University of Illinois we learned about Balakian’s research uncovering his family’s experiences during and after the Genocide as well as how he personally negotiates the inheritance of traumatic memories and speaks about this past. Through his engagement with international communities, Balakian has fascinating insight on memory work that crosses borders, developing dialogues between Armenians and other minority groups in Turkey.

Throughout his visit, Balakian tasked individuals interested in the study of genocides to consider such far-reaching effects of humanitarian efforts. In 2015, during the centennial commemoration of the Genocide, Balakian recalled watching activists’ global efforts, media coverage of the commemoration and the historic event, and political entities’ formal recognition of the Genocide. He asserted that examples like the New York Times’sfive full page spread with color plates “represented some acute sense of an ethically meaningful moment” and contrasted recent coverage with historical representations and humanitarian outreach. Balakian argued that the “Armenian case provides us with many interesting vectors of study and exploration” in terms of how “the news stays news” and how “the history’s not dead.”

The generous support from The Program in Jewish Culture and Society and The Initiative in Holocaust, Genocide, and Memory Studies made possible Balakian’s lecture and his activities on campus.

Helen Makhdoumian is a Ph.D. student in English at the University of Illinois.