Following Pope John Paul II’s visit to Cuba in 1998, Fidel Castro Ruz convened a symposium to examine religious life in Cuba. Representatives from different religious communities were invited to attend and share their experiences and perspectives. During that event, members of Beth Shalom Congregation (a.k.a El Patronato)—one of three major synagogues in contemporary Havana—invited Fidel to visit their shul. When he asked when he should visit, the Vice-President suggested that he attend their upcoming celebration of Chanukah. “Chanukah, what is that?” the comandante asked. In the seconds she had to come up with a response, the Vice-President told me she had a moment of divine inspiration: “It is the Revolution of the Jews.” she replied. Apparently unable to resist such an invitation, Fidel made an appearance at the Patronato’s Chanukah celebration the following month.

Most of the congregants knew nothing of the invitation, and even the few who did were not necessarily expecting Fidel to actually show up. They insisted he speak; he acquiesced and went up on to the synagogue’s bimma to say a few words—i.e. he spoke for about two hours. (For those of you not familiar with Fidel’s speaking style, he was known for delivering incredibly long speeches. His speech to the General Assembly at the United Nations, for example, is recorded as having lasted about 4.5 hours. Of course, this pales in comparison to his longest speech in Cuba, purportedly lasting over 7 hours.) At the Patronato, he displayed his newly acquired understanding of Jewish history: Castro delivered an extended exegesis on the socialist lessons of the Macabees, peppered the congregants with questions, and directed them toward the appropriate bibliography when they were unable to answer.

Over the years, I have heard several versions of this story. The question of who precisely was responsible for orchestrating the visit is an issue of some debate. Otherwise, however, the basic details in these versions rarely vary. Notably, the affect runs the gamut from childlike wonder to sheer terror. One member told me that he arrived late and, seeing a bearded man speaking from the bimma, initially mistook Fidel for a visiting rabbi. He quickly realized his mistake and thought, “No! It’s the rabbi of rabbis!” Another person present told me that she found the entire experience highly traumatic, and positioned herself as close as possible to the doors at the rear of the sanctuary (which she said were effectively blocked by the myriad of security personnel accompanying Fidel).

Over the years, I have heard several versions of this story. The question of who precisely was responsible for orchestrating the visit is an issue of some debate. Otherwise, however, the basic details in these versions rarely vary. Notably, the affect runs the gamut from childlike wonder to sheer terror. One member told me that he arrived late and, seeing a bearded man speaking from the bimma, initially mistook Fidel for a visiting rabbi. He quickly realized his mistake and thought, “No! It’s the rabbi of rabbis!” Another person present told me that she found the entire experience highly traumatic, and positioned herself as close as possible to the doors at the rear of the sanctuary (which she said were effectively blocked by the myriad of security personnel accompanying Fidel).

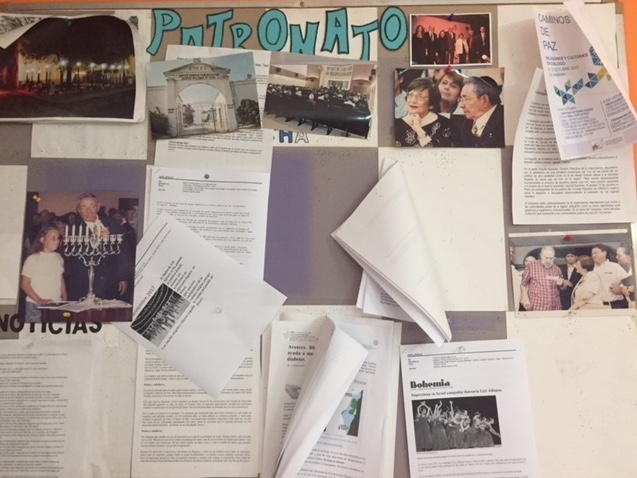

These differences notwithstanding, the story has become a signature feature of the synagogue and its communal history. Visitors are often treated to a version, usually as they are shown the pictures of Fidel's visit that still hang on the main bulletin board. Over the years, I have been afforded snapshots and accounts of other luminaries who also visited the synagogue (Stephen Spielberg in the 90s, Madonna and Justin Trudeau in recent years), but the attachment to these visits has proven more ephemeral. Fidel’s Chanukah sermon—and Raul's subsequent participation in candle lighting, marking the anniversary of his brother's historic visit—endure.